New technology from Montreal researchers could greatly benefit the lives of children and adults with heart defects.

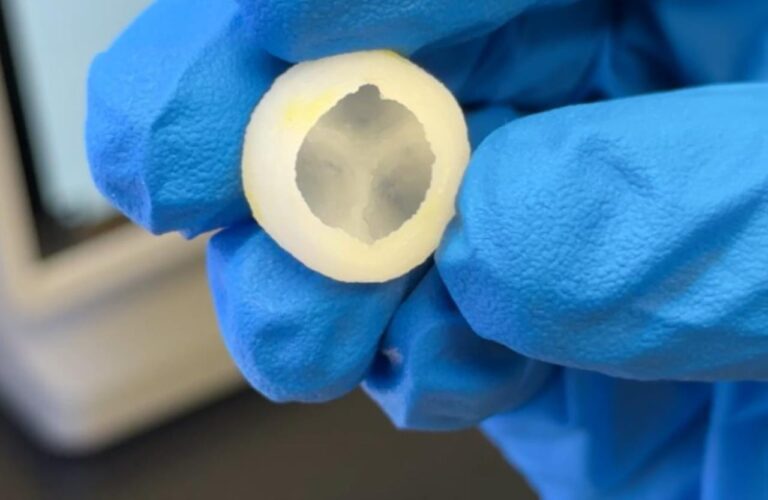

Researchers at Sainte-Justine Hospital are using 3D printers to make heart valves – and it only takes about an hour.

Behind the new technology are Université de Montréal PhD student Arman Jafari and Sainte-Justine Hospital principal investigator Dr. Houman Savoji.

“If this can be implanted in a person and that person can live even a couple of years more in a good condition, that’s really what excites me,” Jafari told CityNews.

“We were hoping to actually address a clinical need,” added Savoji, who is also an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at UdeM.

Savoji explains the 3D-printed valves can grow with the children during their lifetime.

“And another thing is that the bodies themselves can remodel the valve and can make their own cells, can make their own home,” he said.

The process involves a composite ink made of different polymers being added into the 3D printer’s cartridge. The valve is then designed on the printer’s software.

“And then using this machine, which is a cutting-edge 3D printer, we are able to use that design that we had, and in a layer by layer manner, we print a 3D structure,” Jafari said.

Damaged heart valves are usually replaced with mechanical valves or ones from animals, but the researchers say that comes with risks.

“As a child, you grow relatively fast until you get to the adulthood,” Jafari said. “And over time, so your heart is growing and your heart valves also should grow. But when you replace your heart valve with the current option, there is this problem that the valve cannot grow with the child.”

That can lead to multiple, “very invasive” surgeries during a lifetime, Houman adds.

The researchers say some 90 patients receive synthetic valves at Sainte-Justine Hospital each year.

The research could have other uses as well.

“With the 3D printing, the sky is the limit,” Jafari said. “So if there is a burn patient, maybe you can use the same ink. And if you test it, maybe you can use it as a skin patch to help the patient recover faster. It can be for muscles, for example, if you change it a little bit. Yes, so I can say there could be potentials for it.”

The researchers already have their eyes on the next steps – from animal testing to human trials.

“Around one year to two years, we’re going to finish the medium-sized animal studies,” said Houman. “And then we apply for more funding to do large animal studies in the next three to five years. So probably in the next five years we will finish the pre-clinical testing in animals and then hopefully once we have everything we have to file for regulatory approval.”

Source: montreal.citynews